Beyond Automation: Using Agents to Level Up Your Mind

Agentic workflows are rapidly moving from theory to practice. We now have access to comprehensive libraries of agentic patterns and real-world feedback from engineering teams (like these learnings from Sourcegraph).

But first, what exactly is an agent? It is generally defined as 1:

A system designed to perceive its environment, reason about how to achieve a specific goal, and then take actions to complete it, often with little to no human intervention.

As we all know, this isn’t just an LLM that responds with text; it is a model with access to tools like web search or code execution.

However, this autonomy creates a hidden risk: The Operator’s Dilemma. The more efficient our agents become at “doing,” the more passive we become as observers. If we aren’t careful, we risk becoming passive observers and losing the very skills that made us capable of directing the agents in the first place.

The challenge narrows down to one constant question:

How can the operator use agents to foster their own growth?

The following strategies prioritize self-growth over raw productivity. Our brain has an impressive capacity to learn. By offloading the “thinking” without a strategy, we waste that capacity. Learning provides benefits beyond just your career, including improved mental health 2.

To make this practical, actionable suggestions are included below. You can follow along by just opening a few free Gemini or ChatGPT sessions.

Note: This guide is intentionally kept simple. While agentic workflows can get technically complex, the patterns below are designed to be “copy-paste” friendly so they can be used immediately without any special software. The prompts below are sourced from the BMAD method, named after its creator Brian Madison. BMAD is selected here because it mirrors a professional software development lifecycle (SDLC) more closely than other frameworks. If you use these prompts, please attribute them to the author.

Separate By Scale And Stage, Not Expertise

Trying to separate agents by expertise (e.g., ‘The Python Expert’) tends to limit them. If you think about it, it doesn’t make sense. If you ask an astrobiologist a question, asking them to “pretend they only know astronomy” doesn’t help you. It just restricts the resources they can draw upon.

Conversely, allowing an agent to traverse scale is counter to how we think. We don’t try to understand how a car works by thinking about the molecular structure of rubber tires at the same time we’re thinking about the steering rack. We want the agent to be as knowledgeable as possible, but focused on the right level of abstraction.

These two concepts have specific names in the literature:

- Scale: Hierarchical Task Decomposition

- Stage: Discrete Phase Separation

Scale Example: Hierarchical Task Decomposition

In software, we handle scale by moving down a hierarchy. This prevents the “Developer” agent from getting bogged down in “Product” questions.

In the BMAD method, this looks like this:

- Goal: The Product Manager writes a PRD.

- System: The Architect defines the high-level constraints.

- Task: The Scrum Master breaks it down.

- Execution: The Developer writes the code.

Stage Example: Discrete Phase Separation

Interleaved with Scale is the concept of operating in Stages. Early on, we aren’t sure what we want, so we follow a pattern of Research → Plan → Execute.

In BMAD, this separates the work into distinct phases so you don’t start coding before you know what you are building:

- Research: The Analyst helps you create a brief.

- Plan: The Product Manager, Architect and Scrum Master help you break it down into tasks.

- Execute: The Developer executes the work.

Agents don’t “remember” well across massive contexts 3, so writing things down at each scale and stage, and passing those documents to the next agent, is critical.

Try this: Copy and paste these prompts in different sessions in order. At the end of each session, have the previous agent write a “handover doc” for the next one. Analyst → Product Manager → Architect

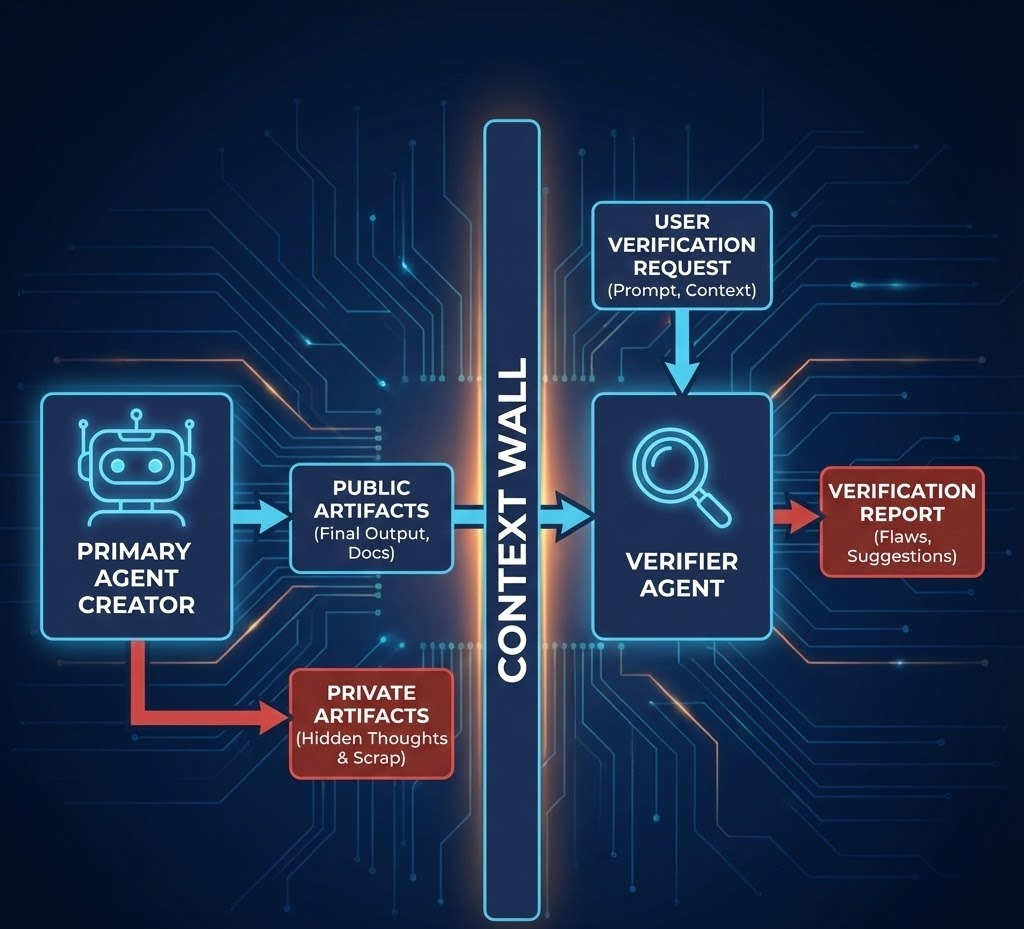

Always Use a Verifier Agent

For every agent performing a task, use a Verifier Agent to check the work. To avoid “sunk cost bias” or the agent simply agreeing with itself, the Verifier must follow three rules:

- Must start from a fresh context (a new chat).

- Must not see the private “thought process” of the first agent.

- Must have a specific prompt focused on finding flaws.

This mimics the real-world “fresh pair of eyes” effect.

Examples from BMAD:

- Scrum Master verified by Product Owner.

- Developer verified by QA Agent.

Automate Only The Scale You’re Comfortable With

When starting, it’s tempting to let agents run wild. This is almost always a mistake. You will quickly lose understanding of the product being built. Instead, think of the agent as a facilitator.

The line of automation should meet your level of expertise. If you let an agent write code you don’t understand, you aren’t growing. You are just accumulating technical debt you can’t pay off. A useful framework is to categorize agents into three levels:

1. Q&A Helper Agent

An agent you ask at least 10 questions a day. Even if you think you know the answer, ask. This is about discovering “what you don’t know you don’t know.”

Try this: Ask an agent “How does transmission fluid work?” or “Why do stars twinkle but planets don’t?” Then (and this is the important part) ask two follow-up questions about the mechanics.

2. Facilitator Agent

These agents brainstorm and ask you questions. They help pull the best ideas out of your head.

Try this: Use the Analyst Agent and tell it you want to build a new app. See how it challenges your assumptions.

3. Autonomous Execution Agent

The agent that does the work. Junior developers should use this sparingly, mostly for code completion. Senior developers can offload larger chunks of routine tasks.

Try this: Ask an agent to write a Python script for a unicorn maze. Crucially: Ask the agent to explain the logic behind the pathfinding algorithm it used so you understand the “why” behind the code.

Keep It Simple

Unless you’re shipping a product, cap your “workflow improvement” time to 10%. The Bitter Lesson and the Wait Calculation suggest that general methods usually win over complex, hand-tuned workflows.

If you spend all your time developing a grand workflow, you risk:

- Being superseded by a simpler, native LLM update.

- Creating a system so complex you never actually use it for real work.

Closing Thoughts

As we develop more and more complex agentic systems, we must remember what drove us here: the desire to learn. Learning and thinking are such integral parts of human behavior that they will be here to stay while humans exist, even if it means we eventually merge with machines 4.

We are at a pivotal moment. We have tools that can think on scales that handle the mundane, enabling us to maximize our learning. But if used incorrectly, simply to “finish the work,” our cognitive skills will decline.

A recent study found that users who used ChatGPT to write essays became “metacognitively lazy.” However, the group that practiced without AI first, and then used AI, performed significantly better.

This leads to the concept of the The Agentic Ladder:

- Master the skill manually so you have a solid footing.

- Use the agent to launch you to the next rung of complexity.

- Repeat.

If you start on a rung you haven’t mastered, you have no footing, and the agent is carrying you. The goal isn’t to build a better agent: it’s to use the agent to build a better version of yourself.

Don’t let the agent be your replacement. Let it be the floor you stand on while you reach for something higher.

Interesting Reading

- The BMAD Method by Brian Madison: The core system used for the prompts in this post.

- Agentic Patterns: A comprehensive catalog of common agent behaviors.

- The MIT ChatGPT Study: On the metacognitive effects of AI assistance.

- The Bitter Lesson by Rich Sutton: A fundamental read on why general methods eventually win in AI.

- The Lazy Tyranny of the Wait Calculation by Ethan Mollick: Why waiting for better AI is often smarter than building complex tools now.

- Context Window Anxiety: Observations on model performance and context awareness.

- Sourcegraph Team Learnings: Real-world insights from engineering teams building with agents.

-

This was taken from GeeksforGeeks. ↩

-

Newer models are sometimes suspected of being aware of their own context window, which can hurt their performance. This is a phenomenon currently called “context anxiety”. This is another reason why separating by scale is vital: smaller, focused contexts keep the agent (and the human) from feeling overwhelmed. ↩

-

A reference to this intriguing prediction ↩